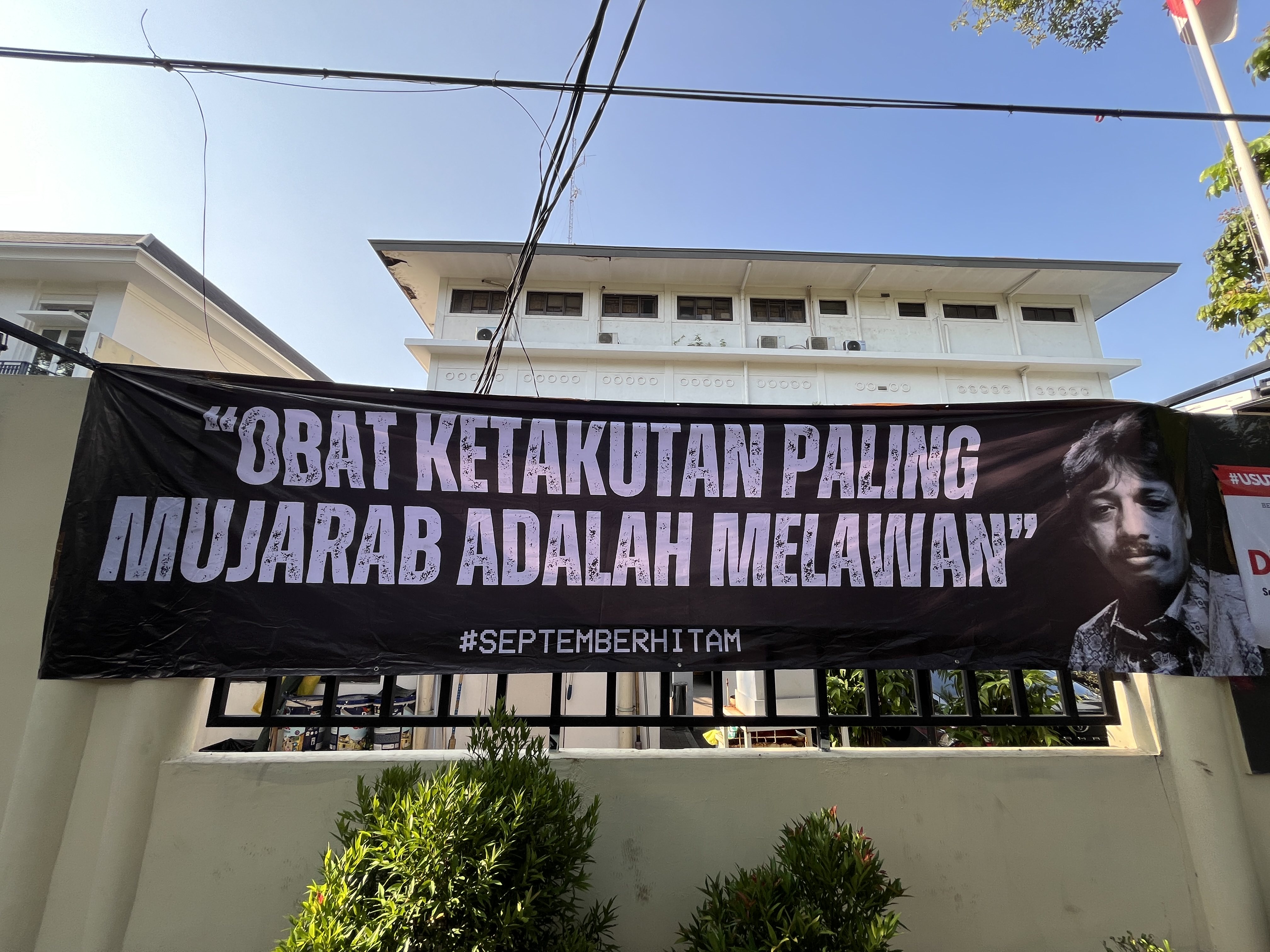

doubts that the Government and the House of Representatives (DPR) genuinely support Komnas HAM’s pro justitia investigation into the Munir case, which has remained stagnant for more than 21 years.

Furthermore, amid the absence of support from the Government and the DPR, KASUM notes emerging attempts by certain parties to delegitimize and discredit the reopening of the mentioned case. According to KASUM, these parties fail to comprehend the nature of serious human rights violations, how such cases must be investigated, and how they must be prosecuted. Munir’s assassination was not an ordinary crime and should not be treated as such by the justice system.

From indications of political elite intervention in the DPR pressuring the leadership of Komnas HAM not to continue the investigation into the Munir case, to the public remarks made by the Director of the Center for Human Rights Studies at the University of North Sumatra (Pusham USU), Alwi Dahlan Ritonga, regarding Komnas HAM in addressing the Munir case investigation.

We also suspect that certain internal elements within Komnas HAM themselves are reluctant to proceed with the pro justitia investigation of the Munir case. This creates the risk that the case will end without meaningful results, not only because of external political obstacles, but also because of the lack of genuine commitment from Komnas HAM.

Regarding the latter point, in a statement published by local media outlet Detik Sumut on Tuesday, 25 November 2025, in an article titled “Director of Pusham USU Says Komnas HAM Misconstrues the Munir Case,” Alwi accused Komnas HAM of committing three “misconceptions” in its efforts to reopen the Munir case. These claims are not only legally incorrect, but also risk obscuring the substance of the long struggle against impunity.

More than two decades after Munir’s assassination in September 2004, the victim’s family, civil society, and the international community continue to demand the fulfillment of the right to truth and justice. In this context, Alwi’s criticisms - alleging three “misconceptions” by Komnas HAM - must be refuted with sound arguments grounded in human rights principles, national law, and international legal standards.

1. Misunderstanding Ne Bis In Idem and the Context of the Munir Case

Alwi argues that Komnas HAM’s first “misconception” is a violation of the principle of ne bis in idem, referring to Article 76 of the Indonesian Criminal Code (KUHP) and Article 14(7) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibit a person from being tried twice for the same offense. According to him, reopening the Munir case after the final convictions of Pollycarpus and Indra Setiawan constitutes a violation of legal certainty and a potential abuse of authority.

This argument contains fundamental logical and legal errors. Ne bis in idem applies only to ordinary crimes, not to extraordinary crimes such as gross human rights violations. Even if certain individuals have previously been tried, convicted, or acquitted, this does not mean they can never be prosecuted again. The principle does not apply to the entire set of actors, events, or the broader construction of the crime. In the Munir case, the key actors suspected of ordering or planning the assassination have never been prosecuted at all.

The court proceedings only reached the field-level perpetrator and an airline official, while the alleged involvement of state actors and decision-makers has never been examined through legal processes.

Moreover, both national and international legal frameworks explicitly allow and even oblige the state to reopen investigations when there are indications of gross human rights violations or systematic efforts to conceal the case.

Indonesia’s Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights requires the state to ensure effective investigation and prosecution of serious human rights violations, while Law No. 26 of 2000 on the Human Rights Court provides Komnas HAM with the authority to conduct pro justitia investigations when there are indications of gross human rights violations. Not a single provision states that ne bis in idem prevents the investigation of such violations, nor does it restrict renewed investigations of individuals who have never been prosecuted.

Under the international human rights standard, the ICCPR in fact affirms that states are obligated to investigate serious human rights violations thoroughly and effectively, especially where there is suspicion of impunity or a miscarriage of justice. The “right to truth,” as reinforced by the UN Human Rights Committee and the UN Human Rights Council, obliges states to ensure that victims and the public know the truth about serious human rights violations, including who is responsible.

Therefore, Alwi’s claim that Komnas HAM is violating ne bis in idem is not only unfounded, but ignores the core principles of human rights law, which demand comprehensive investigation of those most responsible. Komnas HAM is, in fact, fulfilling its constitutional mandate, including by examining key figures such as the former Deputy V of BIN, Muchdi PR, who has never undergone a thorough inquiry within the framework of gross human rights violations.

2. Misunderstanding the Elements of “Gross Human Rights Violations” in the Munir Case

Alwi’s second criticism is that the Munir case does not meet the elements of crimes against humanity as defined under Law No. 26 of 2000 on the Human Rights Court nor the Rome Statute. According to Alwi, gross human rights violations require a “widespread and systematic” attack against a civilian population, typically exemplified by cases such as the Rumah Geudong torture site or other mass-violence events. Because the Munir case involves only a single victim, he argues that this requirement is not met.

This view is overly narrow, ahistorical, and inconsistent with developments in international jurisprudence. The Rome Statute clearly uses the phrase “widespread or systematic,” meaning these characteristics are alternative, not cumulative. The killing of Munir shows indications of meeting the systematic requirement, meaning it was carried out according to a pre-established plan or policy. In Munir’s case, there was organized planning, methodical preparation, and the use of state instruments and facilities in executing the killing.

Several strong elements in the Munir case indicate state involvement and high-level coordination: the use of a state-owned commercial aircraft as the execution site, the involvement of airline officials, the alleged involvement of intelligence officers, the disappearance of state documents, weak tracking of key witness testimonies, and a series of actions that obstructed the investigation.

In addition, the political context of Munir’s assassination cannot be separated from his work as a human rights defender who was critical of state security institutions. The UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders affirms that the killing of a human rights defender is a serious violation that obliges the state to conduct an independent and continuous investigation. Thus, categorizing Munir’s case as an ordinary murder ignores the structural and political context surrounding it.

Alwi’s argument is not only normatively incorrect, but it also risks normalizing impunity for political crimes committed against human rights defenders.

3. Misinterpretation of “Lack of Independence” within Komnas HAM

Alwi’s third alleged “misconception” concerns the supposed lack of independence within Komnas HAM, referring to media reports quoting Komnas HAM Chairperson Anis Hidayah, who stated she would be willing to resign if the investigation into the Munir case were not completed. According to Alwi, this statement reflects psychological hesitation that could compromise the objectivity of the investigation.

This argument is very weak in a methodological sense. First, the independence of Komnas HAM is structural, guaranteed by Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights and by the Paris Principles, the international standard for national human rights institutions. Institutional independence is not determined by public statements made by the chair or commissioners, but rather by the institution’s internal mechanisms, its system of collective decision-making, its standards for fact verification, and its framework for public accountability.

The statement made by the Chair of Komnas HAM should be understood as an expression of urgency regarding the resolution of the case, and it cannot be used as a basis for assessing the quality of the investigation. Ultimately, Komnas HAM’s investigation will be tested through subsequent legal processes, including by the Attorney General’s Office and in court, not through speculative analysis.

Thus, using the personal remarks of the Komnas HAM Chair as a framing device to delegitimize the investigation constitutes an ad hominem argument that is irrelevant to Komnas HAM’s ongoing efforts to investigate the Munir case.

Drawing from the existing considerations, KASUM reaffirms that:

-

Komnas HAM is acting in accordance with its legal mandate in reopening the Munir case as an alleged gross human rights violation;

-

Criticism that undermines the investigative efforts runs counter to human rights principles and to the state’s obligation to ensure truth and justice;

-

The government must fully declassify and release the report and documents of the Fact-Finding Team (TPF) on the Munir case, cease all forms of delegitimization toward Komnas HAM, and ensure institutional support for the continuation of the investigation.

Twenty one years have passed since Munir was murdered. Justice must not be obscured by misleading opinions or legally baseless rhetoric. The state has a non-negotiable obligation: it must resolve the Munir case fully and ensure that all actors, including state actors, are held legally accountable.

Jakarta, 8 December 2025

Committee for Solidarity Action for Munir (KASUM)

Usman Hamid (Chairperson)

Bivitri Susanti (Secretary General)

KontraS

Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan