President Prabowo Subianto has recently been reported to pursue a major agenda in his administration to improve Indonesia’s law-enforcement system, including through police reform. As is known, the plan was subsequently followed up by establishing the Committee for Accelerating Police Reform, which was formalized through Presidential Decree (Keppres) Number 122/P of 2025 on the Appointment of Members of the Committee for Accelerating the Reform of the Indonesian National Police on 7 November 2025, although there are several notes and criticisms regarding its membership composition.

Instead of carrying out police reform, the Government and the House of Representatives (DPR RI) instead drafted and accelerated the passage the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP) which will strengthen the police’s monopoly on authority and discretion, further turning it into a superpowered institution, while mechanisms for checks and balances or oversight of the police are increasingly weakened. This situation has unfolded not long after the establishment of the committee intended to carry out comprehensive reforms of the police.

The failure to achieve professional and accountable policing practices, as well as the ongoing failure of police reform efforts, cannot be separated from the failure to properly regulate police authority and to design effective oversight (checks and balances) mechanisms for the police in which the mentioned matters have been governed under Law No. 8 of 1981 on the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP).

Under the previous provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP), various cases of torture, wrongful arrest, fabricated charges, criminalization, abuse of power, undue delays in handling cases, and discrimination in law enforcement frequently occurred and were carried out by the police in performing their constitutional duties and functions. These problems have often been documented in reports by various civil society organizations and independent state institutions.

Meanwhile, the current draft of the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP) further strengthens police control and monopoly of authority, as well as expanding its discretion, which will only perpetuate various forms of abuse of power, failures in law enforcement, and practices of impunity within the police force. Thus, the Government’s and the House of Representatives’ plan to enact the new KUHAP will merely create a dead end, firmly closing the door, and even obstructing the much-touted discourse on police reform.

Several concerning provisions in the draft revision of the Criminal Procedure Code (KUHAP) and have the potential to shut down efforts toward police reform are included in the articles below:

-

The police are becoming even more of a super-powered institution. All Civil Servant Investigators (PPNS) and Special Investigators are placed under police coordination, turning the Indonesian National Police (Polri) into a superpower institution with enormous control (Articles 7 and 8);

-

The inclusion of undercover buy operations (covert purchasing) and controlled delivery (supervised shipment) conducted by the police, which previously investigative powers were limited to special crimes (such as narcotics cases), has been inserted arbitrarily into the draft revision of Criminal Procedure Code (RKUHAP) as investigative methods that can be applied without limitation to all types of crimes and without judicial oversight (Article 16). Such broad-unsupervised authority creates the potential for entrapment, enabling the fabrication or creation of criminal acts against anyone;

-

Coercive measures such as searches, seizures, and account blocking may be carried out without a court warrant on the grounds of an “urgent situation,” based solely on the police’s subjective assessment (Articles 105, 112A, and 132A). The draft KUHAP also grants investigators the authority to conduct wiretapping without a judge’s authorization, based on a law that does not yet even exist (Article 124);

-

Everyone becomes increasingly vulnerable to extortion and being coerced into “amicable settlements” under the pretext of restorative justice, even in the opaque, unregulated space of police investigations. Article 74a of the draft KUHAP states that a peace agreement between the perpetrator and the victim may be carried out at a stage where the existence of a criminal act has not even been established (the investigation stage);

-

The neglect of citizens’ reports is likely to persist within the police. Article 23 of the draft revision fails to resolve the problem of citizen reports that are not followed up (undue delay) by the police. This article merely regulates the internal reporting flow within the police, without specifying any obligation to follow up, nor any time limits for handling complaints;

-

Article 5 of the draft allows investigative police officers, at the investigation stage, to carry out arrests, travel restrictions, searches, and even detention, even though at this stage a criminal act has not yet been confirmed.

Given the substance of the draft revision of Criminal Procedure Code (RKUHAP) and the fact that the Government and the House of Representatives (DPR RI) continue to push for its passage, it is clear that this legislative agenda will only perpetuate the failures of police law-enforcement practices and undermine the government’s stated plan to pursue police reform.

Therefore, we, the Civil Society Coalition for Police Reform, urge President Prabowo and the Indonesian House of Representatives (DPR RI) to withdraw the current RKUHAP draft and postpone its enactment, at the very least by taking into account the ongoing discourse on police reform.

Jakarta, 17 November 2025

Civil Society Coalition for Police Reform

-

The Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI)

-

Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW)

-

Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) Indonesia

-

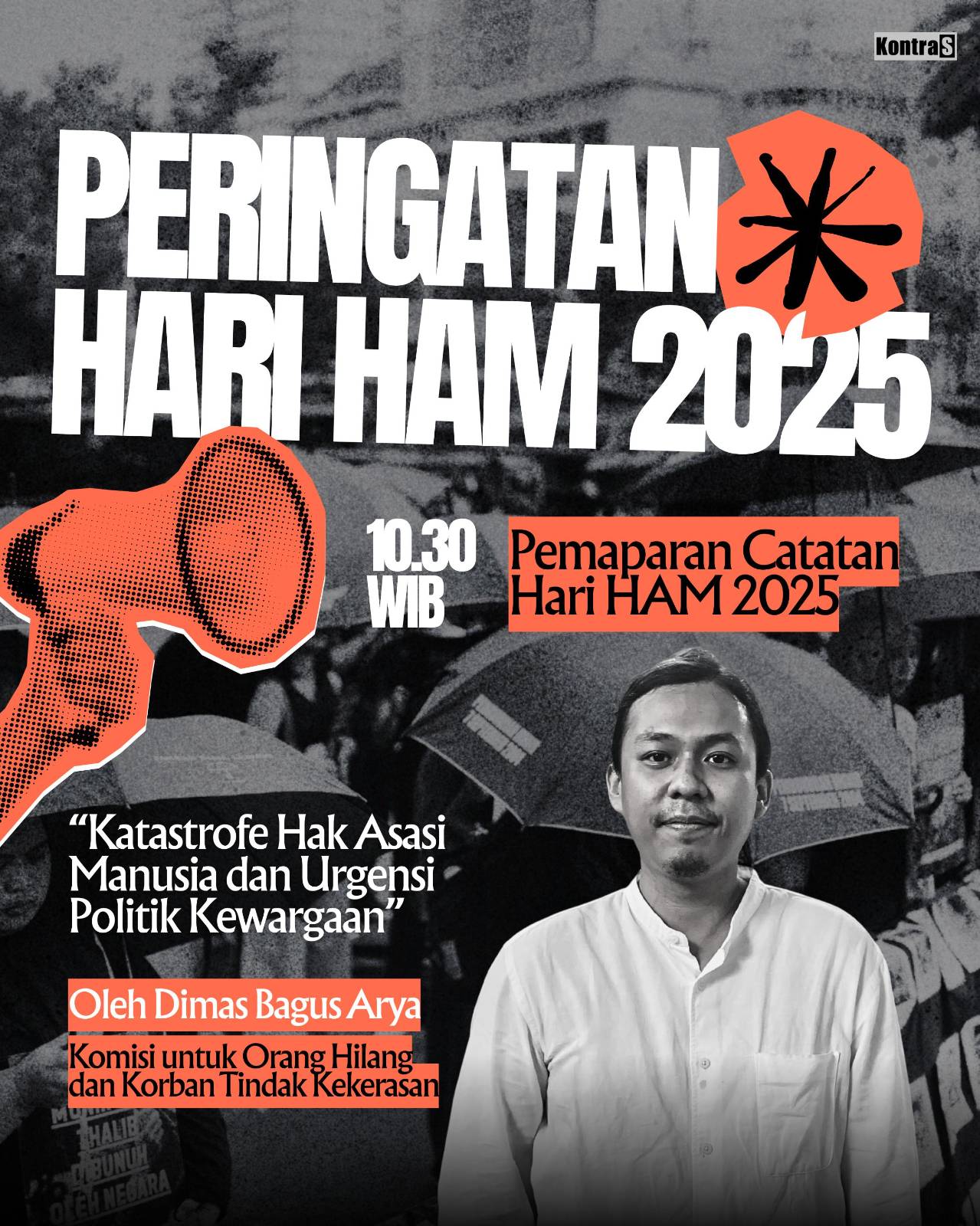

The Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence (KontraS)

-

Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR)

-

Indonesian Legal Aid and Human Rights Association (PBHI)

-

Kurawal Foundation

-

Legal Aid Institute (LBH Masyarakat)

-

Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network (SAFEnet)

-

Jakarta Legal Aid Institute (LBH Jakarta)

-

Center for Indonesian Law and Policy Studies (PSHK)

-

Press Legal Aid Institute (LBH Pers)

-

Indonesia Judicial Research Society (IJRS)

KontraS

Komisi Untuk Orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan